Introduction

AWS has made much progress over the years with IPv6 support. From S3, EC2, Cloudfront, Route53, and EC2 support back in 2016, to more recent updates to NLB and the EC2 API, I’ve appreciated every advancement and patiently waited for the next. Unfortunately, there are still pieces missing that prevent me from making full use of IPv6 in my employer’s current environment.

Existing architecture

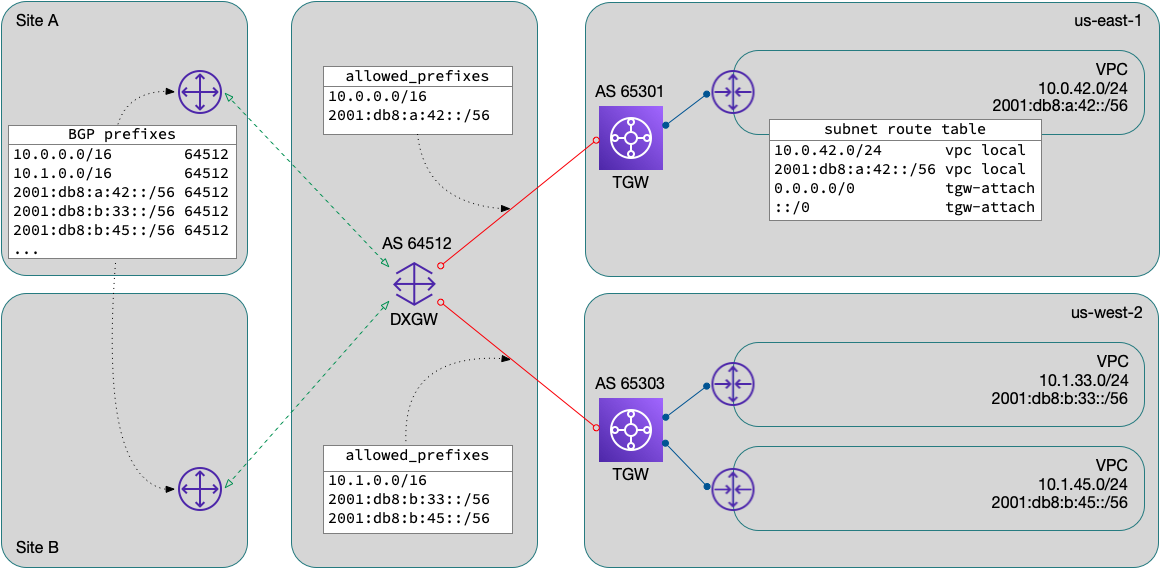

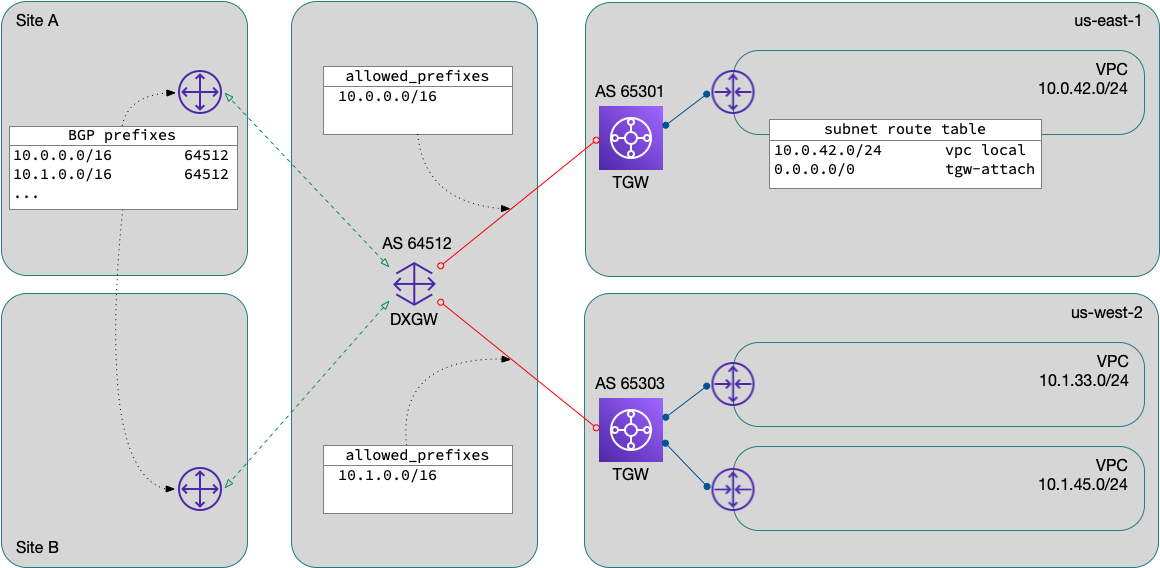

The architecture is modeled after one of AWS’s recommended connectivity designs. VPCs attach to a per-region transit gateway (TGW) for access to each other, shared services, on-prem network, our Azure VNets, and Internet access. In practice, a set of TGW route tables (common, campus, etc.) allow association and propagation with and to these various routes.

The connectivity to on-prem (and Azure) is via AWS’s Direct Connect service. Each regional TGW connects to the Direct Connect gateway (DXGW) using a TGW Association. Transit VIFs are provisioned from the DXGW to each DX router.

In the interests of simplification, I’ve omitted or changed many components and other details such as VPN backup, Direct Connect provider infrastructure, IP addressing, and on-prem networking.

Routing

Traffic from the VPC is statically routed with entries for either

0.0.0.0/0 or more specific prefixes and a destination of the TGW

attachment in each subnet’s route table. Traffic to the VPC is

controlled by the propagation of the VPC’s CIDR blocks to one or more

TGW route tables.

Routing between the DXGW and on-prem uses BGP. The DXGW is a global

construct, and has its own ASN. Each regional TGW also has a unique

ASN. But, there is no dynamic routing between the TGW and the DXGW.

The TGW association has an attribute, allowed_prefixes, which is a

list of networks serviced by the TGW. These networks are injected into

the DXGW route table and propagated to the rest of the network via BGP.

There is a scaling limitation here: allowed_prefixes is (currently)

limited to 20 prefixes (per association). Listing each VPC’s CIDR block

here would unnecessarily limit the number of VPCs you could effectively

attach. Fortunately, a sane IPv4 addressing plan allows us to summarize

these networks on a per-region basis.

IPv6 is different

Note that I said sane IPv4 addressing plan. This is not the case

for IPv6. With IPv4, using RFC1918 address space, we were able to

pre-allocate blocks based on our planned expansion and growth. With

IPv6, all addressing is global. When you create a VPC and use an

“Amazon-provided IPv6 CIDR block”, AWS allocates a /56 out of one of

their public blocks. Now you’re back to the scaling problem of listing

all these blocks in your allowed_prefixes attribute.

AWS does publish a list of their public ranges.

Theoretically, you could list (some of) these blocks in your

allowed_prefixes, but (without some very ugly hacks) would also end up

blackholing traffic to valid public addresses.

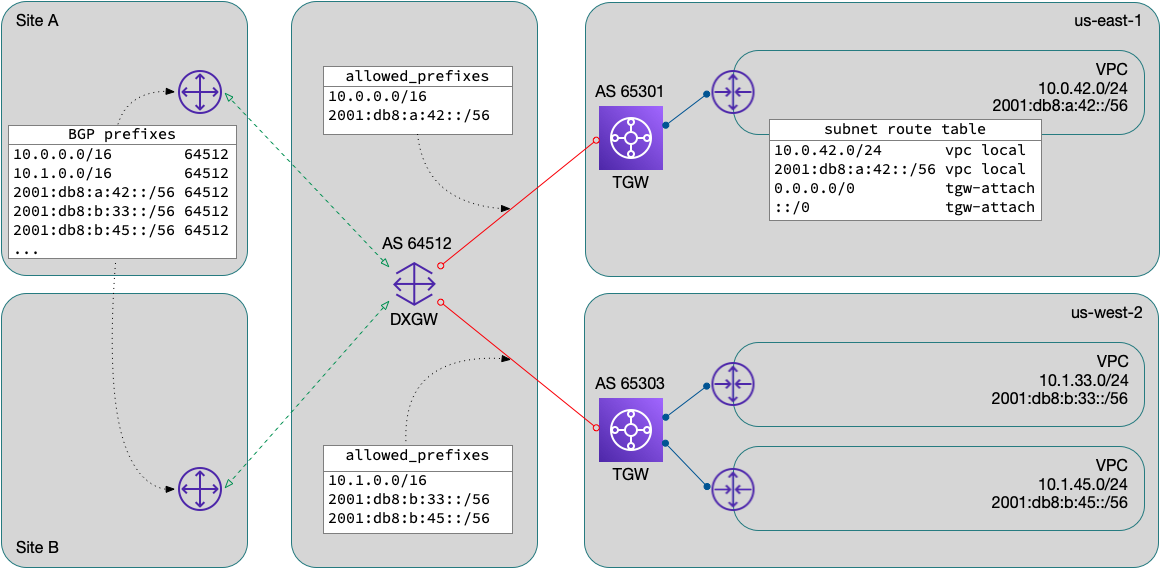

BYOIPv6 to the rescue

I was especially excited when AWS announced

their BYOIPv6 service. Maybe this was the solution I was

wishing for? As soon as it was available, I allocated a /48 to each

region, which is a single additional entry in the allowed_prefixes

list. AWS’s instructions were very straightforward; after

generating a signed RPKI ROA, and submitting a couple API calls,

I was able to add an customer-provided IPv6 block to a VPC and route

to/from on-prem.

At scale

My excitement abated a bit once I tried to deploy this beyond my first couple of VPCs. Currently, AWS does not permit sharing BYOIPv6 blocks across accounts. If all your leaf VPCs are in only a few accounts, it might be feasible to allocate a /48 to each account/region combination. But, again, that pattern falls down quickly as you add more than a dozen accounts or so. Ideally, in my opinion, there would be a mechanism to use AWS Resource Access Manager to share BYOIP blocks to other accounts within your organization.

What next

Shortly after I realized all this, I brought this concern to our AWS account team, who quickly put me in touch with the product manager. As is almost always the case with these types of issues, they were already aware of this limitation. For now, I will hold off on our AWS IPv6 deployment waiting until AWS releases new features that will allow us to solve this.

If you’ve read all this and see something I’ve overlooked or think I have not considered, please reach out. I’d love to hear how others are solving these same issues.